Looking at this painting of Nicholas Loftus, it is easy to think that this is just another painting of a man in a white wig, wearing black clothes. And in one sense you would be right, as there are many similar looking paintings from the time. However, with a little background information and by taking a chance to inspect it more closely, Nicholas’ painting reveals him to be an eighteenth century Irish patriot of substantial political power, concerned with improving Irish agriculture and industry.

The painting by Jacob Ennis was completed in 1757 to celebrate Nicholas’ 70th birthday. In marking this milestone Nicholas used his painting to allude to some of his achievements in life. Written on the white piece of paper by his elbow is his title, Viscount Loftus of Ely, which he had received the previous year. This was not the first time his status had been elevated. In 1751, Nicholas had gotten onto the first rung of the peerage ladder by becoming Baron Loftus of Loftus Hall. Managing to be elevated to Viscount after a few short years as Baron was probably the result of political maneuvering which had been started with his father, Henry, in the seventeenth century. Nicholas built on this and became a master of political wheeling and dealing, leading to the creation of the ‘Loftus Legion’.

The Loftus Legion was essentially a mini party within the Irish Parliament on College Green. Consisting of seats held by various members of the extended Loftus family – fathers, sons, brothers-in-law and cousins – it grew to seven seats by the time of Nicholas’ painting. Some of these seats were held in what was termed as ‘rotten boroughs’. These boroughs were areas which had previously been significant in the medieval period, but had since been greatly depopulated and now the only voters were the holders of the seat and their associates. Bannow and Clonmines, located near the Loftus estate in Wexford, were two such boroughs. And with no opposition, the Loftuses were easily able to hold onto these seats. Moreover, since the Fethard corporation was filled by people who worked for the Loftuses, the seat of Fethard (the seat closest to Loftus Hall) was sewn up as well. By controlling seven of 300 seats in the parliament in Dublin, the Loftus Legion gave the family an outweighed influence in political circles. An influence that would have certainly aided Nicholas’ elevation from commoner to Baron and finally to Viscount.

The Irish parliament of the eighteenth century was one of success and limitation. After the defeat of James II in 1691, the Protestant minority of Ireland had the control of all of the levers of power in the country, especially politically. The Irish parliament was run by ‘undertakers’, so called as they pledged to undertake the will of the King. Over time these undertakers, including Nicholas, felt that the parliament in Westminster had an outweighed influence in the running of Ireland. Due to Poynings’ Law and the Declaratory Act, Dublin’s parliament was essentially subordinate to Westminster. This infuriated many Irish MPs, who felt that MPs in Westminster could not make laws for Ireland as they were not the representatives of Ireland. By the time Nicholas died this patriotic feeling was growing ever stronger. Spurred on by the American and French Revolutions, it led to development of the Volunteer militia movement, Henry Grattan’s famous speech in defence of the Irish parliament, and as a consequence, the removal of both Poynings’ Law and the Declaratory Act. Looking at this movement from the perspective of the twenty-first century, it is important to note that these patriots were not advocating Ireland becoming a republic or breaking Ireland’s connection with Britain.

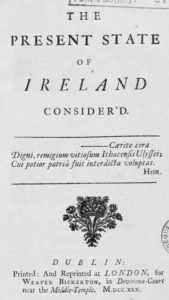

A concern for Ireland’s standing is underlined by a book that Nicholas has under his arm – The Present State of Ireland Consider’d. With the spine of the book facing us, we are expected to notice it and understand its significance. This anonymous pamphlet published nearly thirty years earlier in 1730 dealt with the issue of absentee landlords and the need to develop the economy of Ireland.

Absenteeism was seen as a major problem for the Irish economy, as it led to a flow of money out of the country in the form of rents. In addition, these landlords were not around to invest and develop their estates. The idea of the improving landlord was very popular at the time. It was promoted by the Dublin Society, founded in 1731, and of which Nicholas was a lifelong member. The full name of the society – Dublin Society for improving Husbandry, Manufacturers and other Useful Art and Sciences – demonstrates the priority it placed on agriculture as well as the development of the economy as a whole.

The text also took issue with those in Ireland who spent their money on foreign made luxuries. It stated: ‘If I have 1000l. Per Ann. and Annually lay out 200 in foreign consumable Commodities, necessary only to Luxury, I am one fifth part an Absentee, let me live where I will’. An early advocate for buying Guaranteed Irish! The plain dress of Nicholas can be seen as a comment on those who spent lavishly on exotic fabrics such as silk.

Finally, the anonymous writer took aim at the laws that restricted Ireland’s ability to develop its own industries – mainly the woolen and linen industries. Again we can see Nicholas supporting the argument of the Present State in his dress. He is seen wearing an Irish linen scarf, a marker of those who sought to defend and develop Irish industry. The scarf is also a reference to Nicholas’ position as a Trustee of the Linen Board. The fact that Nicholas wanted to include this text decades after its publication, coupled with its depiction as a full book rather than the pamphlet it was, underlines the importance that Nicholas placed on its arguments.

Although the painting has indicated much about Nicholas’ life and interests, it doesn’t tell us anything about his fascinating personal life. Nicholas had three women in his life, starting with Anne Ponsonby, his first wife, with whom he had two sons (Nicholas, left top and Henry, left bottom) and three daughters. When Anne died Nicholas got remarried to Leitia Rowley. (Leitia was also a widow, having been married to another Loftus – Nicholas’ third cousin once removed. The marriage market was obviously a difficult one!) In addition to this, Nicholas also started an affair with his Catholic housekeeper, Mary Hernon; an affair which lasted over thirty years until his death, and a good explanation for his estrangement from Letitia. Not only did Nicholas have an affair with Mary, but they also had two sons together. While it was definitely not unheard of for upper class gentlemen to have mistresses or even to have children with them, Nicholas’ determination to ensure their position within the Loftus family and preferential treatment of these sons, sometimes to the disadvantage of his legitimate sons, is not typical. Nicholas’ and Mary’s sons – Edward and Nicholas (yes, two of Nicholas’ sons were named after him) were well provided for. They were given the Loftus surname, educated in Trinity and included in his will. It appears that Nicholas cared much more for his ‘illegitimate’ sons, than his legitimate heirs to whom he did not leave any of his possessions. This preferential treatment was especially true of Edward, for whom he arranged a favourable marriage, as well as setting him up with his own estate, Mount Loftus in Kilkenny. As Edward wrote a letter titled ‘On the Culture of Potatoes’ for The Proceedings of the Dublin Society, their good relationship may have been cultivated by a similar interest in agricultural developments and the importance of being an improving landlord.

Although the painting has indicated much about Nicholas’ life and interests, it doesn’t tell us anything about his fascinating personal life. Nicholas had three women in his life, starting with Anne Ponsonby, his first wife, with whom he had two sons (Nicholas, left top and Henry, left bottom) and three daughters. When Anne died Nicholas got remarried to Leitia Rowley. (Leitia was also a widow, having been married to another Loftus – Nicholas’ third cousin once removed. The marriage market was obviously a difficult one!) In addition to this, Nicholas also started an affair with his Catholic housekeeper, Mary Hernon; an affair which lasted over thirty years until his death, and a good explanation for his estrangement from Letitia. Not only did Nicholas have an affair with Mary, but they also had two sons together. While it was definitely not unheard of for upper class gentlemen to have mistresses or even to have children with them, Nicholas’ determination to ensure their position within the Loftus family and preferential treatment of these sons, sometimes to the disadvantage of his legitimate sons, is not typical. Nicholas’ and Mary’s sons – Edward and Nicholas (yes, two of Nicholas’ sons were named after him) were well provided for. They were given the Loftus surname, educated in Trinity and included in his will. It appears that Nicholas cared much more for his ‘illegitimate’ sons, than his legitimate heirs to whom he did not leave any of his possessions. This preferential treatment was especially true of Edward, for whom he arranged a favourable marriage, as well as setting him up with his own estate, Mount Loftus in Kilkenny. As Edward wrote a letter titled ‘On the Culture of Potatoes’ for The Proceedings of the Dublin Society, their good relationship may have been cultivated by a similar interest in agricultural developments and the importance of being an improving landlord.

Studying a portrait, such as Nicholas’, challenges us to identify and understand aspects of the subject’s life. And although there is much to discover in a portrait, as we have seen it does not reveal everything. Nicholas makes no allusion to his family in his portrait. Therefore, we can uncover in a painting only what the subject wanted to highlight. However, looking at what is omitted as well as included may give us further insight into the subject’s motivations and character.

Studying a portrait, such as Nicholas’, challenges us to identify and understand aspects of the subject’s life. And although there is much to discover in a portrait, as we have seen it does not reveal everything. Nicholas makes no allusion to his family in his portrait. Therefore, we can uncover in a painting only what the subject wanted to highlight. However, looking at what is omitted as well as included may give us further insight into the subject’s motivations and character.