A pair of watercolour paintings by George Holmes hang in the Family Drawing Room on the second floor of Rathfarnham Castle.

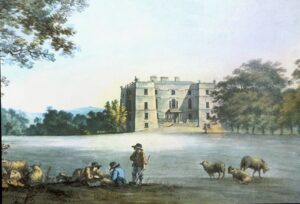

Rathfarnham Castle, Co Dublin, The Principal Front by George Holmes, 1794

The artist’s signature together with the date—1794—are barely visible in the grass just below the group of shepherds in this first one. By framing it in this way the artist used the trees on the righthand side to conceal the coach house, stables, barns, byres and other agricultural and working buildings from our view. The viewer’s gaze is instead directed at the picturesque scene in front of the house complete with shepherds lolling around on the grass. In the companion piece, this time looking from the east, the Castle is visible in the distance with one of the ornamental ponds, several of which once dotted the demesne, positioned in the foreground.

Rathfarnham Castle, Co Dublin, The East Elevation by George Holmes, c.1794

One wonders if the workers on the Rathfarnham Castle estate enjoyed the leisure of sitting around in the middle of the day but perhaps these pictures aim to convey an image and message of contentment. To perhaps promote the idea that the ‘Big House’, residence of Charles Tottenham-Loftus, the Earl of Ely, and its surrounding estate, provided contentment and the good life for all, down even to the lowliest ‘happy peasant’.

As we know, the Irish countryside was anything but happy and contented during the 1790s. Rather, Ireland was gripped by a period of profound and enduring political crisis culminating in the outbreak of republican rebellion in 1798. While the famous events of Wexford in ’98 are much better known today, the initial action was focussed on Dublin and its outlying areas. Indeed groups of armed rebels appeared in Rathfarnham on the very first night of the rebellion, Wednesday 23rd May. The following is an extract taken from The Freeman’s Journal published the following Saturday:

The Freeman’s Journal, May 26th 1798

An action took place on Wednesday night, in the neighbourhood of Rathfarnham, between a considerable body of Rebels who had assembled in that quarter, and a squadron of the 5th Dragoons, who fortunately came up with them. The Rebels were armed with pikes, and were marching towards the metropolis, led on by a young man named Keogh, a resident of that vicinity, and who had good prospects from the industry of his parents. They were unable to withstand the bravery and military skill of the cavalry, who put them to flight, killing and wounding many and made a prisoner of Keogh, their leader, whom they brought to town wounded, and lodged him in the Castle-Guard-house.

Two dead bodies of the same insurgents, who seemed to be officers under the commander, they brought up also to town, who appeared horrid examples of their own rebellious temerity, from the cuts they received from the cavalry. One got a back stroke of a sword across his two eyes and nose that almost divided the head, and had his hands nearly cut to pieces, in endeavouring to guard his head.

The other was killed by another stroke of a sword on the side of the skull that clove it and he received also a ball in the side of the head, and another in the groin. They were well-dressed, able young men, and had the appearance of the sons of respectable country farmers. One of them, we are told, was named Byrne, lived in the neighbourhood of Glasmanogue, and was possessed of a handsome property. Ledwich was the name of the other […].

This newspaper account condensed and greatly simplified what had taken place in Rathfarnham. A few years later a much more comprehensive account, running to several pages, appeared in Richard Musgrave’s Memoirs of the Different Rebellions in Ireland (1801). This work, while strongly biased against the rebels, had access to first-hand testimony and is generally well-regarded by historians of the period for its comprehensiveness and fundamental reliability. Below are a few extracts taken from that work on what had happened in Rathfarnham:

The Breaking-out of the rebellion

The earl of Ely commanded a corps of yeoman cavalry at Rathfarnham, a village about three miles distant from Dublin, of which a serjeant and twelve men mounted guard every night, and patroled through the adjacent country.

Lord Camden [the Lord Lieutenant, John Jeffreys Pratt, 1st Marquess Camden], having received information that the rebels meant to attack and cut off that small party, on the night of the twenty-third of May, 1798, recommended to the commanding officer that the whole troop should mount guard, which, eventually, was very fortunate; for soon after they were assembled, a man, about nine o’clock, went to lieutenant Latouche, who commanded on that night [David LaTouche, of nearby Marlay House], and offered to conduct him to a place where two hundred rebels were assembled; but on arriving there, there was no appearance of them. It proved afterwards, that the design of this traitor was to have led the patrole, consisting of a serjeant and twelve men, into an ambush, by which they would have been cut off; but a numerous body of rebels, who meditated their destruction, intimidated by the unexpected arrival of the whole troop, concealed themselves in adjacent hedges.

This account perhaps suggests that while raised and operating under his name, Lord Ely’s Yeomanry may not have been commanded by Loftus himself (see below) on that night, but rather by David LaTouche.

Charles Tottenham-Loftus, 1st Marquess of Ely by Hugh Douglas-Hamilton, c.1800

Rathfarnham Castle Collection

Musgrave continues:

At their return to Rathfarnham, they were informed by a person, supposed to be connected with the rebels, that the village would be attacked, and that they would be disarmed by a numerous body of them, who were assembling on the mountains.

[…]

The corps, having heard two shots fired, proceeded to Harold’s-cross, and were informed there, that the rebels, about five hundred in number and variously armed, had passed through Rathfarnham in their absence, and had proceeded towards Crumlin, headed by David Keely, a deserter from their troop. Mr. Bennet [An Army Messenger] returned to Rathfarnham in the absence of his troop, and having heard a great shouting at a place called the Ponds, he repaired there, and saw a great concourse of rebels armed with muskets, pikes and pistols, and was on the point of being surrounded by them [The Ponds was an area lying between Rathfarnham Castle and nearby Rathfarnham House (later Loreto Abbey and now home to Gaelcholáiste an Phiarsaigh)]. They had two carts laden with pikes and ammunition, which they were to have distributed among such rebels as should join them in their progress. He therefore, with great fortitude, and with that zealous loyalty which would have procured wealth and fame for a person in a less humble situation, undertook the perilous service of communicating to the viceroy what he had seen; and it was really perilous, for the rebels in great numbers were risen, and were in the road and in the adjacent fields as he went to Dublin. In the city, particularly in the suburbs, he saw a great number of rebels with pikes, in gate-ways, alleys and stable-lanes, waiting the beat of their drums, and the approach of rebel columns from the country, which they expected; and as he passed, they frequently cried out, animating each other, “Come, on boys! who’s afraid?”

A lady, resident at Rathfarnham, informed me, that they passed close by her house, with two carts filled with pikes, which made a dreadful rumbling noise, and which, joined to their yells, filled her with horror. As they proceeded they cried out frequently, “Liberty, and no king!”

Besides the above Keely, they had as leaders two men of the names of Ledwich and Wade, Roman catholicks, and deserters from lord Ely’s corps, Edward Keogh and James Byrne, all of the same persuasion, and in very good circumstances. They proceeded to the Fox and Geese common near Clondalkin, where a numerous body of rebels were to have assembled, and to have proceeded thence to Dublin, for the purpose of co-operating with its disaffected inhabitants, in a general insurrection.

The corps of yeomanry, at their return to Rathfarnham, having discovered that the rebels had risen, immediately sent intelligence of it to the viceroy, who communicated it to the lord mayor, and to the principal civil and military officers in the metropolis, and ordered them to take the most decisive and vigorous measures to defeat the malignant designs of the insurgents [pp.211-12]

[…]

and having been informed at Rathfarnham, that they [the rebels] had gone towards Rathcool, they [troops of the 5th dragoons and Ancient Britons] proceeded in quest of them; and in their way they met a corps of yeomen, who were retreating after having attacked the rebels, and been repulsed by them.

It seems then that the rebels prevailed against Lord Ely’s Yeomanry. Details then follow in Musgrave’s Memoirs on the efforts made by the regular armed forces to subsequently cut the rebels off on the Rathcoole road. It might be that the rebels were trying to gain control of the turnpike road and, perhaps, co-ordinate with United Irishmen from surrounding areas. The turnpike gate on the Naas Road, half a mile from Rathcoole, was kept by one Felix Rourke, a United Irish secretary.

Lord Roden’s [Robert Jocelyn] party came up with them at the first turnpike gate on the Rathcool-road, and after a short skirmish drove them to the place where lieutenant O’Reily was posted; and he having fallen in with them, killed two, and wounded a good many of them, after which the main body made their escape; for the country was so much enclosed, as to prevent the possibility of pursuit.

The bodies of James Byrne and James Keely, two of their leaders, whom they killed, were brought to the castle-yard, and exhibited to publick view; and Edward Keogh, another of their leaders, was brought in there desperately wounded.

Ledwich and Wade, the two deserters from lord Ely’s corps, were hanged on the Queen’s-bridge in Dublin, on Saturday the twenty-sixth of May [p.223].

Mellows Bridge, formerly Queen’s Bridge

Image: Dept. of Housing, Local Government and Heritage

According to another source, while Byrne and Kelly had been ‘killed at Rathfarnham’, ‘their lifeless bodies and three others were hung the morning after their death, from lampirons in Barrack Street [now Benburb Street], and afterwards consigned to “Croppies’ Hole.”’ This detail is taken from a broadside published in the nineteenth century by an apothecary from Ormond Quay, Dr Thomas Willis, who had witnessed the scenes in 1798 as a boy. He descibes the “Croppies’ Acre,” or “Croppies’ Hole” as ‘a piece of waste ground on the south side of Barrack-street selected by the authorities ‘to avoid expensive internment’. The area was ‘waste, and covered in with filth’. ‘Those strangled at the Provost Prison, and on the different Bridges, together with the sabred bodies of the peasantry brought into the City almost daily, were all flung into the trenches formed in that filthy dung heap.’ [Memorial of “Croppies’ Acre”, NLI, EPH E455]. This, then, is where the bodies of several of the rebel leaders who were active in Rathfarnham on 23rd May 1798 ended up.

There is a very brief postscript of some further rebel activity in Rathfarnham about a fortnight later. This, again, is taken from Musgrave’s Memoirs:

On June the ninth, a detachment of captain Beresford’s corps patrolling near Rathfarnham, came up with a party of rebels who were on their way from Dublin to the Wicklow mountains, conveying ammunition to the banditti who infested them. They were armed, and had a green flag and green cockades in their hats. Three or four of them were killed, and three who had acted with singular treachery by firing after they had surrendered themselves, were hanged at Rathfarnham; five more were led into town as prisoners [p.531].

Where exactly in Rathfarnham were these rebels hanged? There is a local tradition that it was on or near the site of Chilham House in the village.

The Act of Union and the closure of the Irish Parliament House on College Green followed swiftly on the heels of the failed rebellion. The members of the House were paid off to vote the Act through and the Earl of Ely, Charles Tottenham-Loftus, profited handsomely. Such was the extent of his landholding and the seats he controlled, that he was eventually induced to vote in favour of the Union on receipt of £45,000 (several million euros in today’s money), together with an elevation in his title. He ended his days no mere Earl, but rather as the Marquess of Ely.

Some further reading:

On the Rebellion more generally:

- Thomas Bartlett, Rebellion (1998)

- Thomas Bartlett (et al.), The 1798 Rebellion: A Bicentenary Perspective (2003)

- Thomas Pakenham, The Year of Liberty: The Great Irish Rebellion of 1798 (1969)

On local events:

- 1798 Rebellion, South Dublin, History and Heritage series (1998), SDCC Library Service publication. Available here: https://source.southdublinlibraries.ie/bitstream/10599/12320/5/1798PDF.pdf

- Richard Musgrave, Memoirs of the Different Rebellions in Ireland (1801) [digitised, searchable copies are available online].

- Patrick Healy, Rathfarnham Roads (2005) p.28 for ‘the Ponds’.

- Violet Broad et al., Rathfarnham: Gateway to the Hills (1990) pp.15-16 re Chilham House.

For Charles Tottenham-Loftus, the Earl and later Marquess of Ely specifically, and on the Loftus family of Rathfarnham Castle more generally, see:

- Simon Loftus, The Invention of Memory (2013)

- P.W. Malcomson, ‘A house divided: The Loftus family, earls and marquesses of Ely, c. 1600-c.1900’, in Dickson and Ó Gráda (eds), Refiguring Ireland: Essays in honour of L.M. Cullen (Dublin, 2003) 184- 221

For maps of the area from this period, see for example the digitised Map Collections at UCD: https://libguides.ucd.ie/findingmaps/mapshistDublin

0524EOF